A Vertical Vision Quest in the San Juan Mountains

By Alex Griffin | October 2025

I put off writing this report for three years. The journals, the photos, the videos—all there. The memories vivid as ever. But the words hadn’t arrived yet.

I ran Ouray 100 in 2022. The experience ran deeper than I knew at the time. It took three years to fully absorb, to settle into my bones.

Now, finally, the words have surfaced. And it’s time to share them.

This isn’t a race report. It’s a journal from the high country. A howl scrawled in altitude and alchemy. A quiet myth etched in tendon and time.

Ouray 100 isn’t a race—it’s a crucible. A back-alley baptism in thunder, lightning, and vertical gain.

I came from sea level with salt in my veins and a storm in my soul. I slept in the dirt, climbed through lightning, bled into the rock. I let solitude carve me open.

The infamous finisher buckle isn’t given—it’s a talisman, a relic of power, earned only through reverence and rage. On the way to claim it, you pass through something ancient. And you don’t come back the same.

By the end, I wasn’t running. I was becoming something elemental. Something formless and free.

Escape Velocity

The beaches of Southern California are not ideal training grounds for a high-altitude mountain ultra—but that’s where the odyssey to Ouray began. The elevation change, both physical and philosophical, is what made the pursuit feel so dynamic, so thrilling.

As my mouse hovered over the ‘Register’ button on UltraSignup, a typhoon spun around in my gut. My hands went damp. My head went light. Adrenaline surged—rare, electric, eerily familiar.

Then—click. ‘Registration Confirmed’

Elevation School

The training began early. I was doing repeats up the steepest hills I could find in North San Diego—Double Peak in San Marcos, Black Mountain in Rancho Peñasquitos, Denk Mountain in Carlsbad. Anywhere I could stack 8,000 to 10,000 feet of vert in a day, I was there. On weekends, I’d be out from dawn ‘til dusk.

My training block was well-balance but hard. As I began really focusing on climbing, I was capturing between 15,000 to 30,000 feet of vertical gain per week on top of a 60-hour work week as a contractor. I was climbing Everest every week—pushing my physical and mental limits, becoming comfortable being uncomfortable.

The timing was perfect. Just as I was finishing up my San Diego contract, climbing and descending had become second nature. With a little over a month until Ouray 100, I put everything else on hold to fully sync with the mountains and the mission ahead.

I wanted my peak training at high altitude. Within three hours of closing out my contract, I was heading north on the 395, bound for the Eastern Sierra.

I set up camp in Onion Valley at 10,000 feet. It hit hard as I made camp. I was instantly fatigued. How could I be so fit and still feel so wrecked?

But I knew: patience. I had been working long, physical hours on top of the high volume training load, and was completely exhausted. Now, I just needed to let the altitude do its quiet work. Let the fatigue settle in and transform me.

Run, rest, and write. That’s it. I wasn’t there to prove anything—I was there to adapt. To listen. And soon, the real work began.

I was doing repeats to Kearsarge Pass and Robinson Lake all day, journaling every mile by the campfire before crawling into my tent each night.

After a few days of contemplating my next move from Onion Valley, I threw my previous plans out the door and headed straight for Colorado—the promised land for sea level neophytes looking to get tough. The initiation from local ultra weenie to big mountain commando. Or so I thought.

I had it all mapped out before. A well-curated plan—squeaky clean, airtight. It looked symmetrical on paper, written out like a final essay I wrote on a college exam: outline, thesis, synthesis, antithesis, and conclusion. Every t crossed and every i dotted with precision. A route planned so thoughtfully, originating completely from my left brain, ignoring my intuition entirely.

As the days slipped by, I started caring less about the itinerary. I was getting scrappy. I was moving more on instinct than analysis. Structure gave way to something raw—more limbic than logical, more marrow than mind. The original blueprint started to blur at the edges, feeling less relevant. More like a scenic detour than a battle plan.

The San Juans were howling in my direction across the Coconino Plateau in a language older than maps. I wasn’t navigating anymore. I was answering.

From the Sierras, I pointed the truck east and drove through the night, only stopping to sleep for a couple hours under the stars, in the moonlit shadow of Wheeler Peak, somewhere out on the Nevada–Utah line. By morning I was in Colorado, chasing vert in the Blue Lakes basin near Telluride.

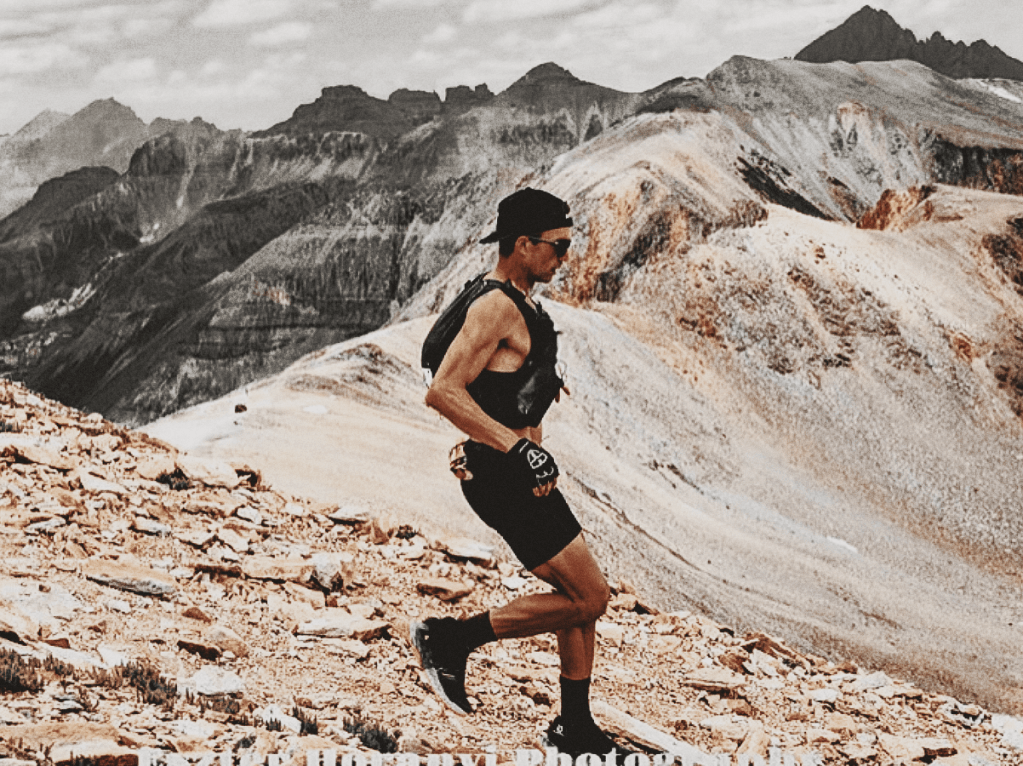

A couple climbs up Mt. Sneffels introduced me to the sharp edge of the San Juans—and it hit different. It felt dangerous, and more exposed. That trip marked something important. I was stepping into a new kind of terrain, physically and mentally. The trip report linked below captures that exact moment in time—a threshold I was crossing. A doorway to Type 2 fun:

High Camp

For the rest of my time in the San Juans, I camped at 10,000 feet in Ironton—just me, the alpine stillness, and the long grind of the final weeks of training. Day by day, I felt myself syncing with the rhythm of the mountains.

The thin air, the wild terrain, the solitude, and the electric pulse of the monsoon season—all of it was rewiring my nervous system to stay calm in chaos, steady in the storm. It was volatile. It was dangerous. And I loved it.

Something novel was emerging: the version of me I’d been visualizing for years. The guy who smiles at the summit, legs wrecked but heart wide open, fully alive and completely free. The one who belongs out here. The one who can do anything.

I was all in. Every night in my tent, I’d strap on the altitude mask—cranked to the highest setting—for about 30 minutes. The mask doesn’t actually simulate ‘altitude’, but it forces you to breathe with intention, pulling air deep from the diaphragm and releasing it in a steady, rhythmic cadence. That practice, combined with living at 10,000 feet for those final weeks, made a big difference.

I was absorbing every podcast I could find on high-altitude performance. One idea stuck with me: a sports doctor said, “Even if you can’t stomach the energy chew or piece of food, just let it sit on your tongue and dissolve—do anything to keep the digestive process moving.” Good advice.

Race Day — Vertical Initiation

On the drive down to the start line, my nervous system began to light up. I couldn’t sit still in the passenger seat—shifting, fidgeting—while trying to play it cool in front of my girlfriend. When we pulled into Fellin Park, my teeth started to chatter, just slightly. It caught me off guard. Everything I’d been suppressing or pushing aside was now rising to the surface, and there was no stuffing it back down.

Just as I stepped out of the car, a text came through from my old friend Rolando—an image of Rambo tying on his headband. I smiled, unexpectedly emotional. That moment reminded me of the friends and family who would be tracking me. And suddenly, everything shifted. My head cleared. I wasn’t alone. Their belief in me lit a fire—transmuting all my tension into raw power. I stood up straighter. I was ready. I wanted to make them proud.

“I’m leaving it all out there.” I said to myself quietly.

I had been here the year before for the 50 miler, but this was much different. The vibe was ominous. The runners looked different. The mountains looked bigger. And I felt smaller.

I wondered how many of us would make it. I even questioned if I belonged out there—surrounded by these fearless mountain goats. But then I remembered the training. The mental preparation. The countless visualizations. The deep personal investment I’d made to finish this race.

I wanted to feel the glory of overcoming. I wanted to raise the bar for myself. This would be the hardest thing I’d ever done in my life—and I wanted the memory of it to live with me forever.

Then, boom… We were off into the San Juans.

The blur of anticipation instantly cut into razor sharp focus. Complexity vanished. All I had to do now was run.

There was the usual jostling on the gentle climb up Camp Bird Road. Some runners I’d see again and again, others I’d never cross paths with.

One of the most memorable was Joseph Holway, a Durango guy—laid-back, with a slight grin, wearing a big sun hat and a floral button-up shirt. I liked him. We’d run into each other many more times throughout the race, trading jokes and laughing about our wild hallucinations.

I knew the course intimately—it had consumed my thoughts, my dreams, and everything in between. The 50-mile route I’d raced the year before made up the entire back half of the 100-mile course, and in training, I had covered nearly every mile of the front half.

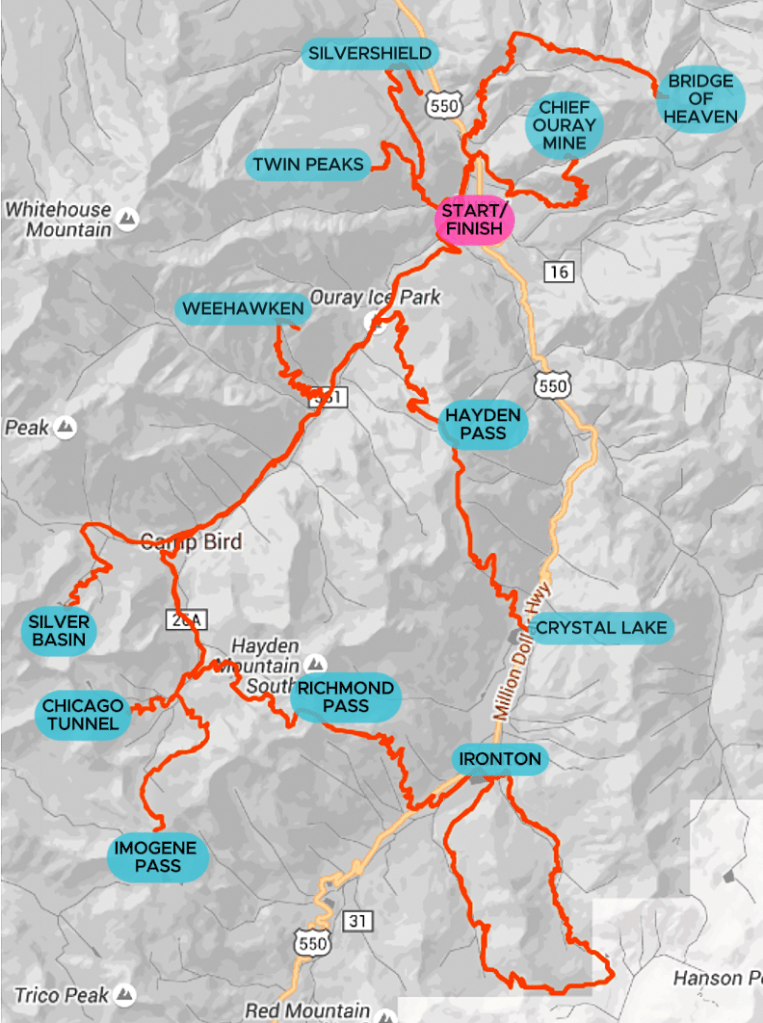

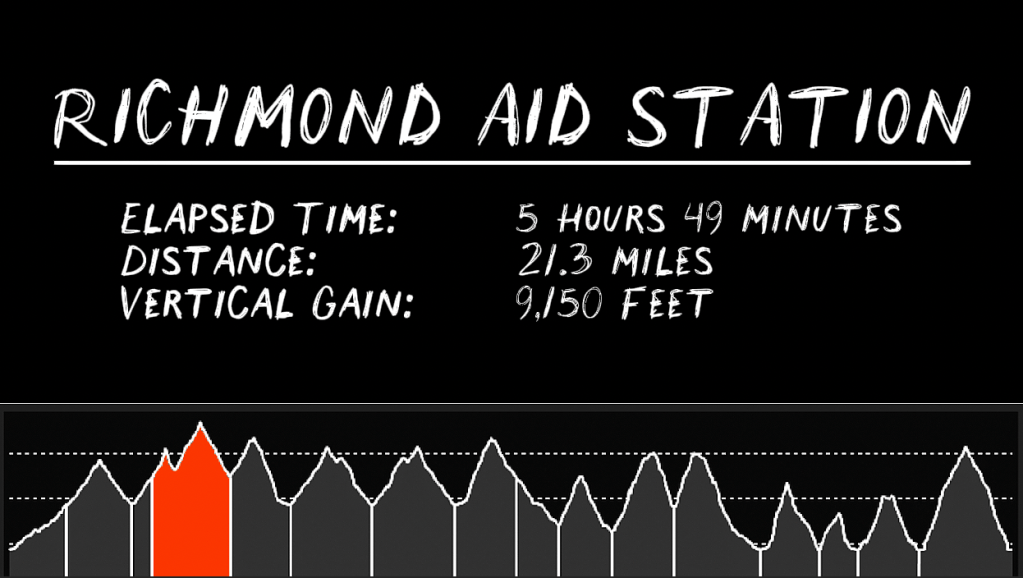

To keep it manageable, I broke the race into distinct sections, with Camp Bird Road acting as the main artery that tied them all together. The first trio of climbs—Silver Basin, Chicago Tunnel, and Imogene Pass—formed the opening gauntlet, with Imogene standing as the highest point of the race at 13,114 feet.

It’s on these out-and-backs that the field starts to stretch and fracture. I remember seeing Miguel Medina already pulling away from the front pack—his stride light, almost effortless, as he descended while I was still grinding my way toward Imogene Pass. This is where I made my first mistake.

Coming down from Imogene Pass had felt better than anything I’d felt in the last 30 miles. The high, the views, the relief—it was intoxicating. But that’s exactly when I should’ve pulled back, staying in control and letting gravity do the work. I didn’t. I pushed—hard.

I was feeling good, maybe too good, and I let that moment carry me too fast, too recklessly. Not long after, climbing up to Richmond Pass, it hit me. I went pale. My shirt clung to me with sweat. I didn’t want to talk to anyone. When Walter Handloser passed me, I just gave him a silent wave, no words, no smile—my spirit was cracked. And I knew exactly why. The descent from Imogene had been careless, driven more by impulsivity and excitement than strategy. Rookie mistake.

I clawed my way up the steep, technical ascent to Richmond Pass, gritting through what had become my first real low of the race. Slowly, I started to come back to life. As I neared the crest, a low rumble echoed through the granite—thunder, distant but unmistakable. Then, just off the edge of my vision, a flicker of lightning split the sky. They’d stopped runners here in years past because of storms. I knew I needed to get off that pass, fast.

As I descended, the storm trailing behind me, I began to notice familiar faces—fellow wolves. A loose, feral pack had formed near the front of the race. The chase pack. Hungry. Rabid. Focused. No words, just shared momentum and grit pulling us deeper into the Ouray mystique.

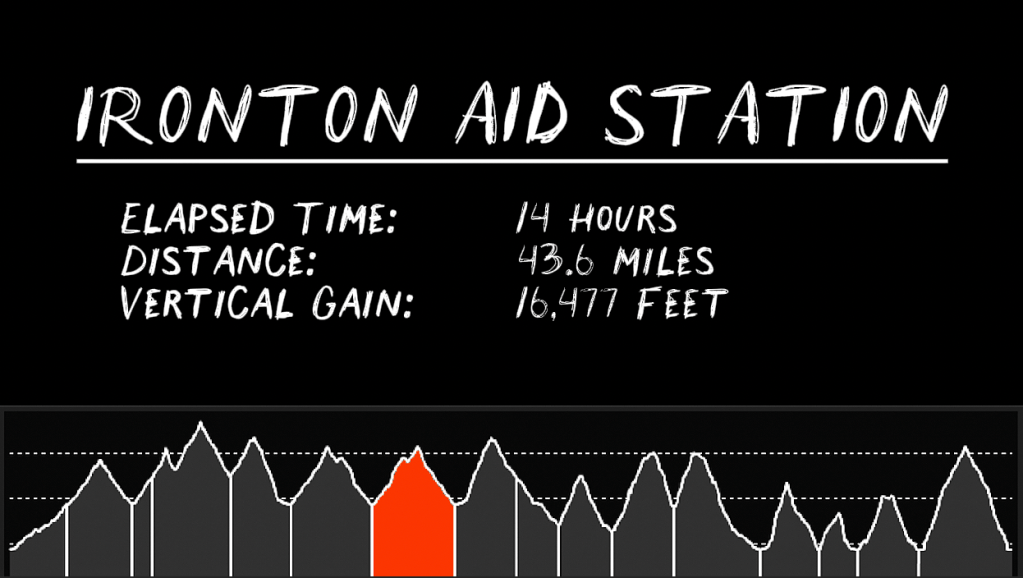

As we began the long, steep, but buttery descent from Richmond Pass, the next section of the race came into view—the double loop around Red Mountain, first in the counter-clockwise direction then back in the clockwise direction. I was camped directly next to the Ironton aid station so this section was very familiar to me.

The climb up through Corkscrew Gulch was my morning run for the last couple weeks and I could actually see my tent during the race. I wanted to climb right in there at that point but I knew it would probably be another 30+ hours before I would get to sleep again if I wanted to finish in the top ten.

The sun was slowly sinking below the horizon—a deep orange with subtle purple streaks hinting at the coming darkness. I felt the shift in energy, that quiet moment before the night takes over.

I was moving well and gaining confidence as some of the front runners began to drop back. The gap between the front and the mid-pack started to widen. You can see exactly where everyone is on this yo-yo format, so I was paying close attention to positioning and how each runner looked.

My breathing was becoming more and more labored at the high points, and my concern was starting to grow. All I wanted was a big gulp of oxygen—but I was only getting tiny little sips. My diaphragm was cooked, and I was breathing more from my chest, hyperventilating every time I got over 12,000 feet. I leaned over my poles, wheezing—drowning in the altitude with no end in sight.

Night began to fall, and the stars slowly peeked through the cosmos as I descended Corkscrew Gulch. I tagged the Ironton aid station for the third and final time. By then, I was feeling pretty good again, but the miles and relentless vertical gain and descent were beginning to take a serious toll on my body.

I was very efficient in the aid stations and probably sat down for about two minutes before I took off again, eating my quesadilla on the go. The half mile section coming out of the Ironton aid station is known for being the only flat section on the entire course. I was in good spirits seeing my girlfriend again who jogged alongside me for a couple minutes. Then as we reached the Richmond Pass Trailhead, I said goodbye and disappeared into the black void, knowing I wouldn’t see her for another 10 hours at Crystal Lake.

It was a quiet 3,000’ climb over the pass and I was bouncing back from the breathing issues I was having. I could see the headlamps swirling around the mountain behind me and realized I was in a decent position seeing many people still just starting their first loop around Red Mountain.

Coming into Richmond Aid Station I was starting to notice some rivalry developing. It’s a race after all and I was there to race. Up to that point, I really wasn’t thinking outside of myself. I was just trying to stay locked in and run as efficiently as I could with minimal time at the aid stations.

After a while, you start to notice people noticing you—that relentless MF, always in your rear view mirror, never letting up. That was me. I wasn’t the fastest guy out there, I was the guy making you work harder than you ever thought you would need to work.

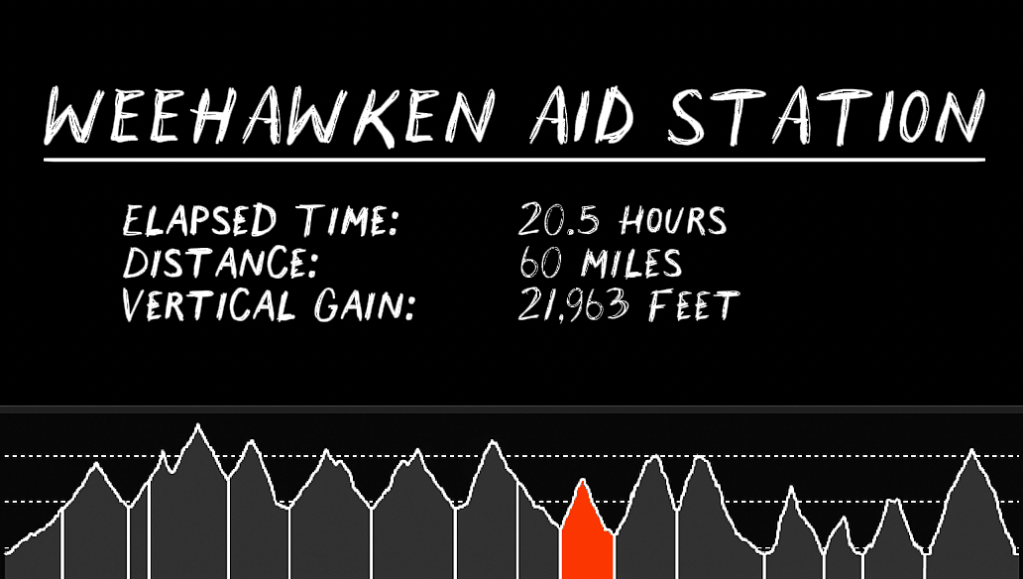

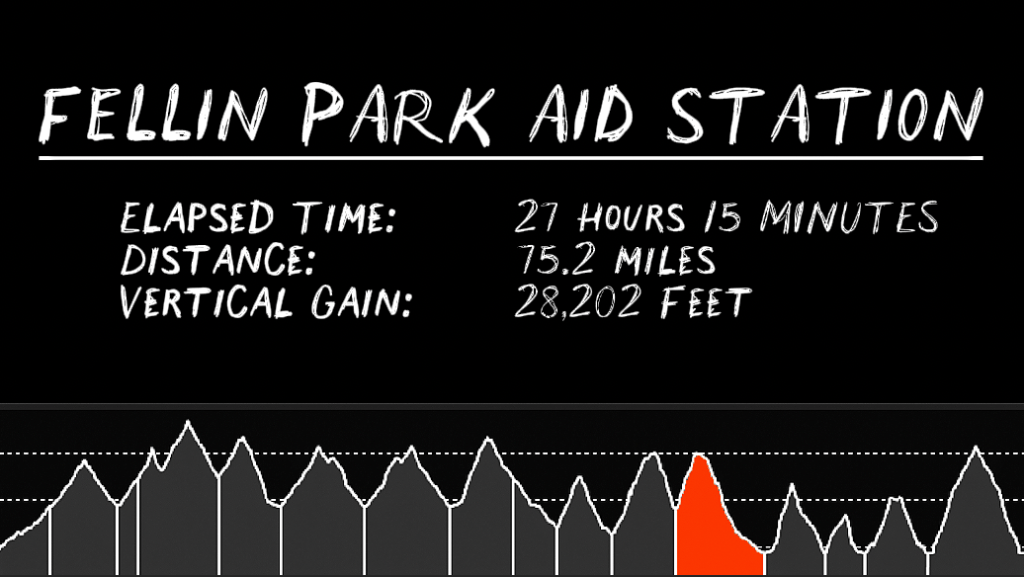

The smooth descent down Camp Bird Road is an inflection point in the race. The first 50 is done. Even though there is a lot more climbing in the back 50, you are now getting closer to Fellin Park, and starting to see a microscopic pinhole of light at the end of the tunnel.

Coming into Weehawken was pretty cool. Kilian Korth and Anthony Lee were running the aid station. Right away, they started calling out stats—my position and the elevation profile for the next two climbs. I’ll never forget that. No encouragement, just math and guidance. That’s exactly what I needed. Not a “you’re crushing it, bro,” or “you’re doing so good.” I wanted the truth. I wanted facts. And as top finishers at Ouray, those two knew exactly what mattered.

After the out-and-back up to the mine, I saw them again. Anthony told me I had posted the fastest split on that section so far. That gave me a real boost. In contrast, I saw a runner I knew from a 50-miler in San Diego a couple years back, telling the staff he was dropping from the race. I was really bummed for him. He didn’t look well—face pale, wrapped in a space blanket, shivering. I wished him well and moved on, full of gratitude for how I was feeling at that point in the race. After all, it was the middle of the night, under the stars, deep in the San Juan Mountains—and I was more than halfway through one of the hardest 100-milers on earth. What could be better?

The Witching Hour

On paper, the climb over Hayden Pass is the second biggest climb of the race. I wasted no time getting started. A quick drop down Camp Bird Road brought me to the trailhead, and then I stepped into the black void.

The darkness was absolute — my headlamp’s small bubble of light was my only tether to the world. I didn’t want to know what lurked beyond that fragile circle. Every little sound was magnified tenfold, sending ripples through my nerves. Fear hovered just beneath the surface, barely held at bay. The relentless effort of the climb occupied my mind enough to keep me grounded.

Completely alone, slipping into the edges of hallucination, I knew it would be hours before I saw another soul. To steady myself, I tuned into some old Art Bell shows from the 90’s I had downloaded, talking about paranormal encounters, bigfoot, and Area 51. Perfect for running through the mountains at night through bear and mountain lion country.

There was Joseph! Just as I crested Hayden Pass, the sun peeked through a cathedral of tall pines, and I saw his silhouette approaching. Every time we crossed paths, our interactions felt meaningful, like we exchanged good energy that carried us forward. He was coming the other way, which meant he’d put about 4–5 hours on me since we last met many hours earlier on Red Mountain. I needed to catch up. I needed to push beyond my comfort zone. I needed to descend fast toward Crystal Lake.

As I began the descent, the sun was rising over the distant mountains, casting a stunning, almost emotional glow. After so many hours swallowed by isolated darkness, that light hit me like a burst of pure energy. I started passing a few runners on the way down, finding a new gear—but something still felt off. My mental state was slipping.

When I arrived at the Crystal Lake aid station and saw my girlfriend, the hysteria I’d been holding back all night suddenly broke through. For the first time in the race, I sat down, burying my face in my folded hands as waves of emotion overwhelmed me. It came out of nowhere. I told her, “I don’t think I can do this anymore.” She said nothing, but looked at me with such quiet strength that I almost instantly stood up and pulled myself together.

These mountains were beating me down hard. I could either collapse, accept defeat, and quit—or I could fight back. I wanted to fight. DNF wasn’t an option, but in that moment, it felt closer than ever.

The decision to move forward was raw and visceral, yet deeply cathartic—like shedding excess weight to keep the ship sailing. I felt energized, both physically and mentally. Back to baseline. Back to the fighter I know myself to be. I was gaining escape velocity, pulling away from the gravity of the start line and letting the tractor beam of the finish line pull me in.

Every runner I passed looked empty, trapped in a dissociated haze—mere shells of their former selves. Survivors, nonetheless. Many had already dropped. We were the few left standing—the stubborn lifeforms still thriving in the radioactive fallout of a nuclear decimation.

Locking Horns

As I descended the far side of Hayden onto Camp Bird Road, there he was—the blonde guy I just couldn’t shake. ‘Johnny’. No matter where I was on the course, he was always there. He didn’t seem friendly. Too serious. No jokes, no banter—just raw ego.

Every time I acknowledged him in passing, he’d ignore me and make these dramatic, guttural breathing noises—some kind of primal territorial display, meant to intimidate competition. I didn’t budge. The tension built steadily throughout the race. It seemed like it was becoming personal.

He was just shuffling down when I first caught sight of him below on the descent from Hayden Pass. I knew instinctively this would be the last time he’d be ahead of me, so I stayed calm. If this was at night, I would’ve turned my light off before he saw me for maximum effect while passing him.

This part of the descent is dangerously steep—you really have to stay locked-in if you don’t want to fall into the gorge. As I closed the gap, he heard me coming and snapped his head around like a startled animal. Our eyes locked. Then he went full send trying to shake me.

I knew we’d be back at Fellin Park soon, so I stayed calm and cool. I kept my pace steady, comfortable—letting him cook his quads thoroughly. This was the crux of the race. When we arrived at Fellin Park, we both sat down at the exact same moment. From that point on, my mission expanded. Finish Ouray in a top ten position, and make sure Johnny is behind you when you do.

I took my time at Fellin Park. If I wanted to break away, I knew I had to nail my fueling and hydration. A top ten finish meant enduring serious discomfort in the miles ahead. There were still 14,000 feet of vertical gain, and with less than 13 hours to cover the next three sections, it was going to be tight—but I believed I could do it. This was racing now. Not just against myself or the course, but against a pack of bloodthirsty mountain orcs, each ready to claw their way into the top ten at any cost.

I couldn’t get comfortable in that chair. It was the middle of the day, the heat was coming on, and my legs were twitching to move. I was beginning to understand that moving at a “comfortable” pace wasn’t going to cut it anymore. If I wanted to break away, I’d have to work for it.

After nearly 30 hours on course, I was sick of the jostling, the silent power plays, the endless game of leapfrog. I wanted to be done with all of it. But instead of letting that frustration eat at me, I turned it into something useful. A big lesson I took away from Ouray: every emotion is fuel and can be transmuted into raw energy. Emotional alchemy meets mountain ultra running.

Chasing Elves

The climb up to Twin Peaks is about as steep as it gets. Rebar held the granite steps in place, spiraling up through the craggy gorge—lush, quiet, and unforgiving. The sun was beaming down through the aspens. The air was thick and wet. Mosquitoes began to swarm in a biblical way, adding their own madness to the moment.

My hallucinations sharpened—edges shimmered into liminal elves, sounds warped into distant voices, and shadows glitched with impossible light. I could feel my nervous system vibrating on the razor’s edge between clarity and collapse.

While my mind melted into psychedelic soup, I could feel my body coming alive. I knew this section of trail well and started moving with real purpose. As a couple front runners came flying down in the opposite direction, I absorbed their intensity, and began to mirror it.

Just as I crested Twin Peaks, I spotted my nemesis just below doing some loud breath work. Just before I passed him on the descent, he finally barked something in a harsh accent: “Ya just can’t get rid of me, ayyy?” I kept my voice low as I lurked behind him: “I’m about to.”

And I did. Leaving Silvershield aid station, I passed him again just as he was rolling in. I wanted to growl at him—but instead, I just took off, legs spinning, mind locked in. I held that intensity through to the finish. This is where I broke away for good.

I shifted my focus. I stopped thinking about who was behind me and started strategizing about what was ahead. That switch in perception, that clean break, was exactly what I needed.

Coming back to Fellin Park, I barely even stopped. My girlfriend handed me a couple gels and a soft flask full of Coca Cola and I was gone. I was running with pure fire headed up to Chief Ouray Mine.

Unintentionally, I PR’d this section during the race having done a pretty hard work out on it just a week before the race. Where was this energy coming from? I was running everything, not even thinking to get my poles out, dunking my head under the waterfall to cool down, maintaining my intensity with an increasingly narrow focus: “Finish strong.”

I tagged the mine, and hammered back down to Fellin Park. This time, I didn’t see the pack I was with earlier until I was half way down the climb. I had put 45 minutes on them at this point and I wasn’t slowing down. I could hear the front runners coming in to the finish line as I ran back into the park. It lit another match and gave me the fire I needed for the final 5,000 ft. climb. I spent no more than two minutes in the aid station and bolted out of their in a hypnotic fury.

Bridge of Heaven

Dusk settled in, painting the shale in a warm orange glow as we started the final climb. This was the blowout—a scar from some violent geological event in the deep past, made of loose shale.

My girlfriend was now pacing me, and having her there was quietly grounding. I was moving well despite the rough start—wretching right in front of her only minutes in. My stomach had been steady the entire race, but now dry heaves came in short bursts as we pushed back up against the thinning air.

This climb is intense. And long. But stunning and rewarding at the highest level. I remembered it very clearly from the year before where I bumped into Jim Walmsley at the peak, pacing Billy Simpson, right at sunrise, with the most stunning view of the San Juans I had ever seen.

This year was different. I had graduated to the next level. I was altogether a different human on this climb. Focused. Determined. More stoic to the pain. More callused to the difficulty. I wanted that shiny bronze buckle. I wanted a new baseline. I wanted the old me to die.

No one was really talking about this race yet. It was punk rock—raw, frenetic, and unrefined. Like the underground thrash band you love and hope no one else ever finds out about. The runners here seemed to share the same quiet code: be brave, but don’t talk about it.

If you wanted the mainstream version, you could skip up the road to Silverton, put your name in the Hard Rock lottery, and maybe get in before your retirement party.

Here, there was no waitlist. No lottery. Just a handful of quiet mountain commandos moving through thin alpine air, Hokas crunching on the loose rock, chasing nothing but internal rewards and the glint of a bronze buckle. The kind of people you don’t know exist until you meet them in the high country—and then you’re glad they’re out there.

Night was falling again, and up ahead I caught the glow of headlamps cresting the final pitch of the Bridge. Joseph and his pacer. Hours ago, he’d been five hours ahead of me—now I was right on his heels. I had no appetite for passing him though. Closing the 5 hour gap felt good enough. On the other hand, holding off the bloodthirsty savage chasing me from behind was imperative.

Just before we hit the final pitch, Joseph swept past with fresh momentum. We traded quick, gritty camaraderie—introducing our pacers, exchanging congrats—and then drifted back into our own parallel adventures.

There we were—on the Bridge of Heaven. I slumped down for a moment, Indian-style, trying to gather myself. Hallucinations swirled, colors warped, shadows bent, emotions surged and crashed, my knees and quads radiating hot pain. Then we dropped back into the tunnel of light, that fragile bubble guiding us downward.

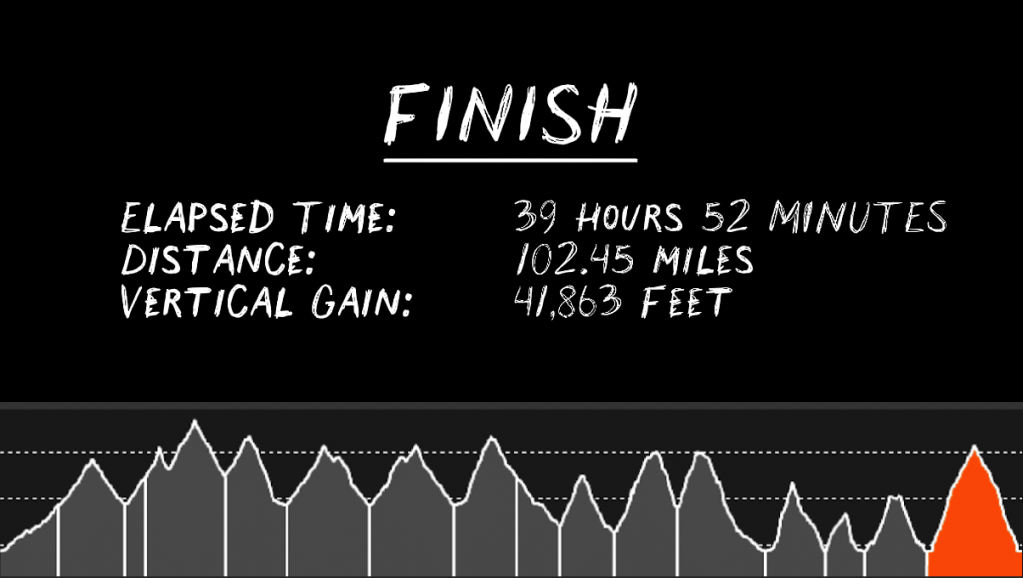

We slipped back into the narrow beam of light guiding us down. My girlfriend was behind me, pushing. Without her, I’d have drifted. I almost never use a pacer, but tonight she was the difference between stumbling and sprinting into the finish. Midnight was the cutoff for sub-40 hours. The only way there was down—through sharp, loose rock, and the collapsing edges of my pain threshold.

Every step echoed up through my central nervous system. My body had no reference for this—no memory, no template. I was in constant adaptation, locked in mortal combat between body and mind, pushing forward in pure defiance of the instinct to preserve myself.

There he was — a wild psychosis burning through bloodshot eyes. Johnny was moving. No words exchanged as we passed. He was an hour and a half back, but moving strong. Adrenaline surged one last time. I was quietly wincing with every step, congratulating everyone runner I saw making the climb up, trying to smile through a contorted face of agony. I was so proud of them all. The camaraderie was palpable. The empathy was direct and pure. I had such tremendous respect for anybody who made it this far.

At last, the spine-tingling 5,000-foot descent was nearly done. We dropped through the blowout, the distant cheers of dwindling spectators echoing as Joseph crossed the finish just ahead. My girlfriend pushed me hard, relentless. “Common Alex you have to move faster!!”

Tiny little jackhammers chiseling away at my tendons. I was so close—I had to sprint. It felt like running underwater, but ahead I saw the gazebo, smoke curling from the grill. I poured everything into my stride, running with the fire of a thousand suns. Then, just minutes before midnight, I crossed through the infamous orange cones, under the pale moonlight. Quiet, still, infinite.

I felt a profound peace as the Co-RD’s Charles Johnston and Chris Marcinek came over to congratulate me. By then, I had almost completely dissociated from my body—barely emotional, just numb. It would take years for the full weight of the race to absorb. For now, an indescribable calm, fulfillment, and relief washed over me. People stood right in front of me, talking, smiling, encouraging—but their voices blurred into distant echoes, their faces just hazy shapes.

I wasn’t really there. My gaze drifted upward, drawn to the mountains, the moon, and the scattered headlamps flickering high above—runners still grinding through the night, fighting their own battles. I felt deep empathy for them, and hoped they would all finish.

Later, sitting with my girlfriend on a quiet terrace in Ouray, nursing a few beers, the adrenaline dump pulsed through me—still vivid, still alive. Ouray 100 was etched deep, immortalized. My former self dissolved completely. I was reborn—novelty piercing through my cracked shell. Now an emergent being, endlessly becoming. Formless. In full surrender to the unknown ahead.

Leave a comment